"These early caregiving bonds are the start to how children grow to understand, trust and form relationships with other people," said Marshall, an associate professor of psychology at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pa.

Marshall is spending the 2014-2015 academic year on sabbatical at the University of Washington's Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences.

Since the beginning of his research career as a graduate student at the University of Cambridge, Marshall has been interested in the ways in which attachments between children and caregivers develop. More recently, he has combined this interest in early bonding with his expertise in the study of early brain development.

"Attachment between infant and caregiver serves as a stepping stone for more complex social connections," he said.

But not all children have this attentive, loving experience.

Marshall saw the "heartbreaking" effects of child neglect about a decade ago, when he was part of a scientific team studying the physical and mental health of infants and toddlers living in Romanian orphanages. Sometimes called an experiment in "zero parenting", the institutionalized children lacked responsive caregivers and the nurturing stimulation that is part of family life.

"Consistent one-on-one attention was pretty much non-existent," Marshall said.

He became involved with the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, which was investigating whether moving the children from orphanages to foster families could remediate some of the damage of early-life neglect.

Marshall went to a Bucharest orphanage in 2000 to set up an EEG laboratory that the researchers could use to study whether the foster family intervention affected the brain.

The research team found significant differences in brain activity between the institutionalized children and children from the community who lived with their families, and that the foster care intervention diminished those differences, as the researchers reported in a 2010 research paper.

His involvement in the study "was eye-opening and made me think more about the effects of early experiences on the brain," Marshall said.

Since then, Marshall has gone to study other aspects of infants' early social development. In 2004 he joined the psychology faculty at Temple, where he directs their developmental psychology area.

In 2007 Marshall met Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of I-LABS, at a conference organized by the National Science Foundation in Arlington, Va. Sharing an interest in how infants develop an understanding of the social world, the two researchers started a collaboration.

"Peter and I started talking about brain and behavior and whether the infant brain measures might be able to be used to test some fundamental aspects of infant imitation that I'd been investigating," Meltzoff said.

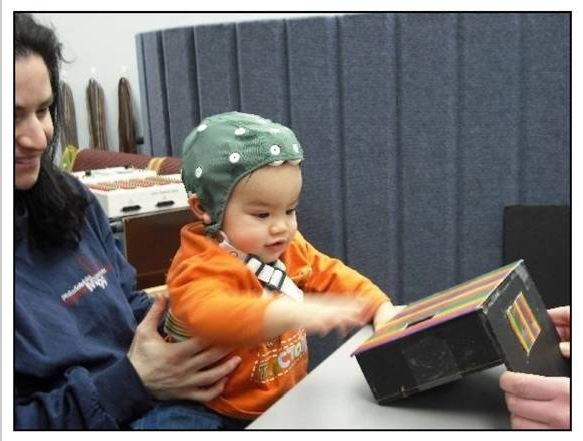

The two researchers have studied how the brain's mu rhythm responds to infants perceiving and producing actions, such as in the image below from a 2011 research paper in Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience.

A summary of their collaborative brain studies was published in April 2014 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

"We’re now hoping to take this much further using the I-LABS MEG brain-imaging capacities," Meltzoff said.

During his time at I-LABS, Marshall and Joni Saby, a post-doctoral researcher, will work with I-LABS' team of MEG experts to more precisely understand how infants develop a body schema, which is related to how parts of the body are represented in the brain.

"We want to study how babies piece together an awareness of themselves as separate from but connected to other people," Marshall said. "This process acts as a foundation for our social connections – our social skills, our ability to make and maintain friendships, and our capacity for empathy."

###

Learn more about the importance of early interactions and emotional development in children through I-LABS' free, online training modules.